Latin spelling and pronunciation

Latin spelling or orthography refers to the spelling of Latin words written in the scripts of all historical phases of Latin from Old Latin to the present. They all use some phase of the same alphabet even though conventional spellings may vary from phase to phase. The Roman alphabet, or Latin alphabet, was adapted from the Old Italic alphabet to represent the phonemes of the Latin language. The Old Italic alphabet had in turn been borrowed from the Greek alphabet, itself adapted from the Phoenician alphabet. A given phoneme may well be represented by different letters in different periods. Latin pronunciation continually evolved over the centuries, making it difficult for speakers in one era to know how Latin was actually spoken in prior eras. This article deals primarily with modern scholarship's best guess at classical Latin's phonemes (phonology) and their pronunciation and writing; that is, how Latin was spoken and spelled among educated people in the late Republic, and then touches upon later changes and other variants.

Contents |

Letters and phonemes

In classical times, each letter of the alphabet corresponded very closely with a phoneme. In the tables below, letters (and digraphs) are paired with the phonemes they represent in IPA. English upper case letters are used to represent the Roman square capitals from which they derive. Latin as yet had no equivalent to the English lower case. It did have a Roman cursive used for rapid writing, which is not represented in this article.

Consonants

Table of single consonants

-

Labial Dental Palatal Velar Glottal plain labial Plosive voiced B /b/ D /d/ G /ɡ/ voiceless P /p/ T /t/ C or K /k/[C 1] QV /kʷ/[C 2] aspirated[C 3] PH /pʰ/ TH /tʰ/ CH /kʰ/ Fricative voiced Z /z/[C 4] voiceless F /f/[C 5] S /s/ H /h/ Nasal M /m/[C 6] N /n/ G/N [ŋ][C 7] Rhotic R /r/[C 8] Approximant L /l/[C 9] I /j/[C 10] V /w/[C 11] Consonant table notes (C 1, 2, 3, etc.):

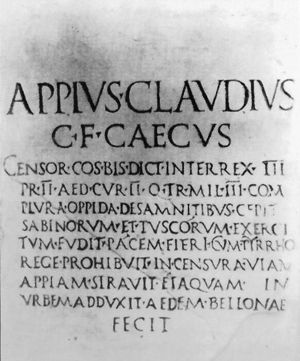

- ↑ ‹C› and ‹K› both represent /k/. In archaic inscriptions of Early Latin, ‹C› was primarily used before ‹I› and ‹E›, while ‹K› was used before ‹A›. However, in classical times, ‹K› had been replaced by ‹C›, except in a very small number of words.[1] ‹q› clarified minimal pairs between /k/ and /kʷ/, making it possible to distinguish between cui /kuj/ (with a diphthong) and qui /kʷiː/ (with a labialized velar stop). ‹X› represented the consonant cluster /ks/, where in Old Latin it had often been used for /ks/, which could be spelled ‹KS›, ‹CS› or ‹XS›. Adding to all this, ‹c› originally represented both /k/ and /ɡ/. Hence, it was used in the abbreviation of common praenomina (first names): Gāius was written as C. and Gnaeus as Cn. Misunderstanding of this convention has led to the erroneous spelling ‹Caius›.

- ↑ In the classical period, /kʷ/ (spelled ‹QV›) became labio-palatalized velar plosive ([kɥ]) when followed by a front vowel. Thus quī was realized as [kɥiː][2]

- ↑ The digraphs representing aspirated phonemes began to be used in writing around the middle of the second century B.C. and were primarily employed for transcribing Greek names and loan-words containing the aspirated sounds represented by phi (‹Φ› /pʰ/), theta (‹Θ› /tʰ/), and chi (‹Χ› /kʰ/), e.g. philippus, cithara, and achaea. In such cases, the aspiration was likely reproduced only by educated speakers.[3] Subsequently, the aspirates began making an appearance in a number of Latin words which were not learned borrowings from classical Greek, initially as allophones of the unaspirated plosives, in proximity to /l/ and /r/. Since ‹CH›, ‹PH› and ‹TH› were already available to represent these sounds graphically, this resulted in standard forms such as pulcher, lachrima, gracchus, triumphus, thereby reducing the phonemes' erstwhile marginal status, at least among educated speakers.[4]

- ↑ /z/ was at first represented by ‹S› or ‹SS› in Hellenistic Greek loanwords (e.g. sena from ζωνη). In the around the second and first centuries BCE zeta (‹Ζ›) was adopted to represent /z/. Based on Italian Greek, where ‹ζ› still represented /dz/, di- and de- before a vowel in Latin was represented Z standing for /dz/: zeta for diaeta. Thereafter Z was either /z/ or /dz/.[5] In classical verse, ‹Z› always counted as two consonants.[6] This might mean that the sound was geminated, i.e. [zː], or pronounced /dz/.

- ↑ The phoneme represented by ‹f› may have also represented a bilabial [ϕ] in Early Latin or perhaps in free variation with [f]. Lloyd, Sturtevant and Kent make this argument based on certain misspellings of inscriptions, the Proto-Indo-European phone which the Latin ‹F› descended from and the way the sound appears to have behaved in Vulgar Latin, particularly in Spain.[7]

- ↑ It is likely that, by the Classical period, /m/ at the end of words was pronounced weakly, either voiceless or simply by nasalizing the preceding vowel.[8] For instance decem ('ten') was probably pronounced [ˈdekẽː]. In addition to the metrical features of Latin poetry, the fact that all such endings in words of more than two syllables lost the final ‹m› in the descendant Romance languages strengthens this hypothesis. For simplicity, and because this is not known for certain, ‹m› is always represented as the phoneme /m/ here and in other references.

- ↑ /n/ assimilated to [m] before labial consonants as in impar < *in-par [impaːr], and to [ŋ] before velar consonants as in quinque [ˈkʷiŋkʷe].[9] Also, ‹g› probably represented a velar nasal before ‹n› (agnus: [ˈaŋnus]).[8][10]

- ↑ The Latin rhotic was either an alveolar trill [r], like Spanish or Italian ‹rr›, or maybe an alveolar flap [ɾ], with a tap of the tongue against the upper gums, as in Spanish ‹r›.[11]

- ↑ /l/ (represented by ‹L›) is thought to have had two allophones in Latin, comparable to many varieties of modern English. According to Allen, it was velarized [ɫ] as in English full at the end of a word or before another consonant; in other positions it was a plain alveolar lateral approximant [l] as in English look.[12]

- ↑ /j/ appears at the beginning of words before a vowel, or in the middle of the words between two vowels; in the latter case, the sound is usually doubled, and is sometimes spelled accordingly (for instance in Cicero and Julius Caesar):[13] iūs [juːs], cuius [ˈkujjus]. Since such a doubled consonant in the middle of a word makes the preceding syllable heavy, the vowel in that syllable is traditionally marked with a macron in dictionaries, although the vowel is usually short. Compound words preserve the /j/ of the element that begins with it: adiectīvum /adjekˈtiːwum/. Note that intervocalic ‹I› can sometimes represent a separate syllabic vowel /i/, such as in the praenomen Gaius [ˈɡaː.i.us].

- ↑ ‹V› and ‹I›, in addition to representing vowels, were used to represent the corresponding approximants. Before a vocalic ‹I› the semi-consonant was often omitted altogether in spelling, for instance in reicit [ˈrejjikit] ('he/she/it threw back').

Double consonants

Double consonants were geminated (‹bb› /bː/, ‹cc› /kː/, etc.). In Early Latin, double consonants were not marked, but in the second century BC, they began to be distinguished in books (but not in inscriptions) with a diacritical mark known as the sicilicus, which was described as being in the shape of a sickle.

Vowels

Latin has five vowel qualities, which may occur long or short, nasal or oral.

Table of vowels

-

Front Central Back long short long short long short High I /iː/, IM /ĩː/ I /i/ V /uː/, UM /ũː/ V /u/ Mid E /eː/, EM /ẽː/ E /e/ O /oː/, OM /õː/ O /o/ Low A /aː/, AM /ãː/ A /a/

Long and short vowels

Each vowel letter (with the possible exception of y) represents at least two phonemes. ‹a› can represent either short /a/ or long /aː/, ‹e› represents either /e/ or /eː/, etc.

Short mid vowels and close vowels were pronounced with a different quality than their long counterparts, being also more open: /e/, /o/, /i/ and /u/ ([ɛ], [ɔ], [ɪ] and [ʊ]).[14]

Short /e/ most likely had a more open allophone before /r/ tending toward near-open [æ].[15]

Adoption of Greek upsilon

‹y› was used in Greek loanwords with upsilon (‹ϒ›, representing /y/). Latin originally had no close front rounded vowel as a distinctive phoneme, and speakers tended to pronounce such loanwords with /u/ (in archaic Latin) or /i/ (in classical and late Latin) if they were unable to produce [y].

Sonus medius

An intermediate vowel sound (likely a close central vowel [ɨ] or possibly its rounded counterpart [ʉ]), called sonus medius, can be reconstructed for the classical period.[16] Such a vowel is found in documentum, optimus, lacrima and other words. It developed out of a historical short /u/ which was later fronted due to vowel reduction. In the vicinity of labial consonants, this sound was not as fronted and may have retained some rounding.[17]

Nasal vowels

Latin vowels also occurred nasalized. This was indicated in writing by a vowel plus ‹M› at the end of a word, or by a vowel plus ‹M› or ‹N› before a consonant, as in monstrum /mõːstrũː/.

Diphthongs

‹ae›, ‹oe›, ‹av›, ‹ei›, ‹ev› originally represented diphthongs: ‹ae› represented /aj/, ‹oe› represented /oj/, ‹av› represented /aw/›, ‹ei› represented /ej/, and ‹ev› represented /ew/. However, soon after the Archaic period, /aj/ and /oj/ lowered the tongue position in the falling element,[18] and started to become monophthongs (/ɛː/ and /eː/, respectively) in rural areas at the end of the republican period.[19] This process, however, does not seem to have been completed before the third century AD in Vulgar Latin, and some scholars say that it may have been regular by the fifth century AD.[20]

Vowel and consonant length

Vowel and consonant length were more significant and more clearly defined in Latin than in modern English. Length is the duration of time that a particular sound is held before proceeding to the next sound in a word. Unfortunately, "vowel length" is a confusing term for English speakers, who in their language call "long vowels" what are in most cases diphthongs, rather than plain vowels. In the modern spelling of Latin, especially in dictionaries and academic work, macrons are frequently used to mark long vowels (‹ā›, ‹ē›, ‹ī›, ‹ō›, ‹ū›), while the breve is sometimes used to indicate that a vowel is short (‹ă›, ‹ĕ›, ‹ĭ›, ‹ŏ›, ‹ŭ›).

Long consonants were indicated through doubling (cf. anus and annus, two different words with distinct pronunciations), but Latin orthography did not distinguish between long and short vowels, nor between the vocalic and consonantal uses of ‹I› and ‹V›. A short-lived convention of spelling long vowels by doubling the vowel letter is associated with the poet Lucius Accius. Later spelling conventions marked long vowels with an apex (a diacritic similar to an acute accent), or in the case of long ‹I›, by increasing the height of the letter. Distinctions of vowel length became less important in later Latin, and have ceased to be phonemic in the modern Romance languages, where the previous long and short versions of the vowels have either been lost or replaced by other phonetic contrasts.

Length was often phonemic in Latin: anus /ˈanus/ ('old woman') or ānus /ˈaːnus/ ('ring, anus').

Syllables and stress

In Latin the distinction between heavy and light syllables is important as it determines where the main stress of a word falls, and is the key element in classical Latin versification. A heavy syllable (sometimes called a "long" syllable) is a syllable that either contains a long vowel or a diphthong, or ends in a consonant. If a single consonant occurs between two syllables within a word, it is considered to belong to the following syllable, so the syllable before the consonant is light if it contains a short vowel. If two or more consonants (or a geminated consonant) occur between syllables within a word, the first of the consonants goes with the first syllable, making it heavy. Certain combinations of consonants, e.g. ‹tr›, are exceptions: both consonants go with the second syllable.

In Latin words of two syllables, the stress is on the first syllable. In words of three or more syllables, the stress is on the penultimate syllable if this is heavy, otherwise on the antepenultimate syllable.

Elision

Where one word ended with a vowel (including a nasalised vowel, represented by a vowel plus ‹M›) and the next word began with a vowel, the first vowel, at least in verse, was regularly elided; that is, it was omitted altogether, or possibly (in the case of /i/ and /u/) pronounced like the corresponding semivowel. Elision also occurred in Ancient Greek but in that language it is shown in writing by the vowel in question being replaced by an apostrophe, whereas in Latin elision is not indicated at all in the orthography, but can be deduced from the verse form. Only occasionally is it found in inscriptions, as in scriptust for scriptum est.

Latin spelling and pronunciation today

Spelling

Modern usage, even when printing classical Latin texts, varies in respect of ‹I› and ‹V›. Many publishers (such as Oxford University Press) continue the old convention of using ‹I› (upper case) and ‹i› (lower case) for both /i/ and /j/, and ‹V› (upper case) and ‹u› (lower case) for both /u/ and /w/. This is also the convention used in this article.

An alternative approach, less common today, is to use ‹I› and ‹U› only for the vowels, and ‹J› and ‹V› for the approximants.

Most modern editions adopt an intermediate position, distinguishing between ‹U› and ‹V› but not between ‹I› and ‹J›. Usually the non-vocalic ‹V› after ‹Q› or ‹G› is still printed as ‹U› rather than ‹V›, probably because in this position it did not change from /w/ to /v/ in post-classical times.[21]

Textbooks and dictionaries indicate the length of vowels by putting a macron or horizontal bar above the long vowel, but this is not generally done in regular texts. Occasionally, mainly in early printed texts up to the 18th century, one may see a circumflex used to indicate a long vowel where this makes a difference to the sense, for instance Româ /ˈroːmaː/ ('from Rome' ablative) compared to Roma /ˈroːma/ ('Rome' nominative).[22] Sometimes, for instance in Roman Catholic service books, an acute accent over a vowel is used to indicate the stressed syllable. This would be redundant for one who knew the classical rules of accentuation, and also made the correct distinction between long and short vowels, but most Latin speakers since the third century have not made any distinction between long and short vowels, while they have kept the accents in the same places, so the use of accent marks allows speakers to read aloud correctly even words that they have never heard spoken aloud.

Pronunciation

Post-Medieval Latin

Since around the beginning of the Renaissance period onwards, with the language being used as an international language among intellectuals, pronunciation of Latin in Europe came to be dominated by the phonology of local languages, resulting in a variety of different pronunciation systems.

Loan words and formal study

When Latin words are used as loanwords in a modern language, there is ordinarily little or no attempt to pronounce them as the Romans did; in most cases, a pronunciation suiting the phonology of the receiving language is employed.

Latin words in common use in English are generally fully assimilated into the English sound system, with little to mark them as foreign, for example, cranium, saliva. Other words have a stronger Latin feel to them, usually because of spelling features such as the digraphs ‹ae› and ‹oe› (occasionally written as ligatures: ‹æ› and ‹œ›, respectively), which both denote /iː/ in English. In the Oxford style, ‹ae› represents /eɪ/, in formulae, for example. The digraph ‹ae› or ligature ‹æ› in some words tends to be given an /aɪ/ pronunciation, for example, curriculum vitae.

However, using loan words in the context of the language borrowing them is a markedly different situation from the study of Latin itself. In this classroom setting, instructors and students attempt to recreate at least some sense of the original pronunciation. What is taught to native anglophones is suggested by the sounds of today's Romance languages, the direct descendants of Latin. Instructors who take this approach rationalize that Romance vowels probably come closer to the original pronunciation than those of any other modern language (see also the section below on "Derivative languages").

However, other languages—including Romance family members—all have their own interpretations of the Latin phonological system, applied both to loan words and formal study of Latin. But English, Romance, or other teachers do not always point out that the particular accent their students learn is not actually the way ancient Romans spoke.

Ecclesiastical pronunciation

Because of the central position of Rome within the Roman Catholic Church, an Italian pronunciation of Latin became commonly accepted. This pronunciation corresponds to that of the Latin-derived words in Italian, and in some respects to the general pronunciation of Latin everywhere in the Middle Ages.

The following are the main points that distinguish ecclesiastical pronunciation from Classical Latin pronunciation:

- Vowels are long when stressed and in an open syllable, otherwise short.[23]

- The digraphs ‹AE› and ‹OE› represent /ɛ/.

- ‹C› denotes [tʃ] (as in English ‹ch›) before ‹AE›, ‹OE›, ‹E›, ‹I› or ‹Y›.

- ‹G› denotes [dʒ] (as in English ‹j›) before ‹AE›, ‹OE›, ‹E›, ‹I› or ‹Y›.

- ‹H› is silent except in two words: mihi and nihil, where it represents /k/. However, the silent ‹H› is regional, as ‹H› is fully pronounced in North America in all cases, e.g., in the phrase da nobis hodie from the Pater Noster.[24]

- ‹S› between vowels represents /z/;[25] when followed by a ‹C› before ‹AE›, ‹OE›, ‹E›, ‹I› or ‹Y›, they represent /ʃ/.

- ‹TI›, if followed by a vowel and not preceded by ‹S›, ‹T›, or ‹X›, represents [tsi].[26]

- ‹V‹ as /u/ is clearly distinguished from the consonant /v/, except after ‹G›, ‹Q› or ‹S›, where it represents /w/. /v/ is now distinguished from the other two sounds in writing (‹V›, as opposed to ‹U›)

- ‹TH› represents /t/.

- ‹PH› represents /f/.

- ‹CH› represents /k/.

- ‹Y› represents /i/.

- ‹GN› represents /ɲ/.

- ‹X› represents /ks/, the /s/ of which merges with a following ‹C› that precedes ‹AE›, ‹OE›, ‹E›, ‹I› or ‹Y› to form /ʃ/, as in excelsis — /ekʃelsis/[26] ‹X› may sometimes be articulated as /ɡz/ at the end of certain words like REX /reɡz/ and before some long vowel sounds.

- ‹Z› represents /dz/.

In his Vox Latina: A guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin, William Sidney Allen remarked that this pronunciation, used by the Roman Catholic Church in Rome and elsewhere, and whose adoption Pope Pius X recommended in a 1912 letter to the Archbishop of Bourges, "is probably less far removed from classical Latin than any other 'national' pronunciation".[27] Pius X issued a Motu Proprio in 1903 making the Roman pronunciation the standard for all liturgical actions in the Church meaning that any Catholic who celebrates a liturgy with others present be it the Mass, a baptism, or the Liturgia Horarum, then they are to use this pronunciation. The ecclesiastical pronunciation has since that time been the required pronunciation for any Catholic performing an action of the Church and is also the preferred pronunciation of Catholics whenever speaking Latin even if not as part of liturgy. The Opus Fundatum Latinitas is a regulatory body in the Vatican that is charged with regulating Latin for use by Catholics similar to the way Académie française regulates the French language within the French state.

Outside of Austria and Germany it is the most widely used standard in choral singing which, with the rare exception like Stravinsky's Oedipus rex (opera), is concerned with liturgical texts. A startling occurrence was its use in the motion picture The Passion of the Christ.[28] Anglican choirs adopted it when classicists abandoned traditional English pronunciation after World War II. The rise of HIP and the availability of guides such as Copeman's Singing in Latin has led to the recent revival of regional pronunciations.

Because it gave rise to many modern languages, Latin did not strictly "die"; it merely evolved over the centuries in diverse ways. The local dialects of Vulgar Latin that emerged eventually became modern Spanish, French, Italian, etc.

Key features of Vulgar Latin and Romance include:

- Almost total loss of /h/ and final /m/.

- Monophthongization of /aj/ and /oj/ into /e/.

- Conversion of the distinction of vowel length into a distinction of height, and subsequent merger of some of these phonemes. Most Romance languages merged short /u/ with long /oː/ and short /i/ with long /eː/.

- Loss of marginal phonemes such as aspirates (/pʰ/, /tʰ/), and /kʰ/) and the close front-rounded vowel [y] in all environments.

- Loss of /n/ before /f/ and /s/[29] (CL sponsa > VL sposa), though this phenomenon's influence on the later development of Romance languages was limited due to written influence and learned borrowings[30].

- Palatalization of /k/ before /e/ and /i/, probably first into /kj/, then /tj/, then /tsj/ before finally developing into /ts/ in loanwords into languages like German, /tʃ/ in various Italian dialects, /θ/ or /s/ in Spanish (depending on dialect) and /s/ in Catalan, Occitan, French and Portuguese. French and some dialects of Occitan had a second palatalisation of /k/ to /ʃ/ (French ‹ch›) or /tʃ/ before Latin /a/[31].

- Palatalization of /ɡ/ before /e/ and /i/, and of /j/, into /dʒ/, then into /ʒ/ in Catalan, Occitan, French and Portuguese. French (and Occitan, but partially) underwent a second palatalisation, of /ɡ/ before Latin /a/[31].

- Palatalization of /ti/ followed by vowel (if not preceded by s, t, x) into /tsj/, then /sj/ and /s/ in Catalan, Occitan, French and Portuguese, /θ/ in Castilian Spanish, /ts/ in Italian.

- The change of /w/ (except after /k/) and, between vowels, /b/ into /β/, then /v/ (in Spanish, [β] became an allophone of /b/, instead).

Examples

The following examples are both in verse, which demonstrates several features more clearly than prose.

From Classical Latin

Virgil's Aeneid, Book 1, verses 1–4. Quantitative metre. Translation: "I sing of arms and the man, who, driven by fate, came first from the borders of Troy to Italy and the Lavinian shores; he [was] much afflicted both on lands and on the deep by the power of the gods, because of fierce Juno's vindictive wrath."

- Ancient Roman orthography (before 2nd century)[32]

- arma·virvmqve·cano·troiae·qvi·primvs·aboris

- italiam·fato·profvgvs·lavinaqve·venit

- litora·mvltvm·ille·etterris·iactatvs·etalto

- vi·svpervm·saevae·memorem·ivnonis·obiram

- Traditional (19th century) English orthography

- Arma virúmque cano, Trojæ qui primus ab oris

- Italiam, fato profugus, Lavináque venit

- Litora; multùm ille et terris jactatus et alto

- Vi superum, sævæ memorem Junonis ob iram.

- Modern orthography with macrons (as Oxford Latin Dictionary)

- Arma uirumque canō, Trōiae quī prīmus ab ōrīs

- Ītaliam fātō profugus, Lāuīnaque uēnit

- lītora; multum ille et terrīs iactātus et altō

- uī superum, saeuae memorem Iūnōnis ob īram.

- Classical Roman pronunciation

- [ˈarma wiˈrũːkᶣe ˈkanoː ˈtroːjjae kᶣiː ˈpriːmus ab ˈoːriːs

- iːˈtaliãː ˈfaːtoː ˈprofuɡus, laːˈwiːnakᶣe ˈweːnit

- ˈliːtora muɫt ill et ˈterriːs jakˈtaːtus et ˈaɫtoː

- wiː ˈsuperũː ˈsaewae ˈmemorẽː juːˈnoːnis ob ˈiːrãː]

Note the elisions in mult(um) and ill(e) in the third line. For a fuller discussion of the prosodic features of this passage, see Latin poetry: Dactylic hexameter.

Some manuscripts have "Lavinia" rather than "Lavina" in the second line.

From Medieval Latin

Beginning of Pange Lingua by St Thomas Aquinas (thirteenth century). Rhymed accentual metre. Translation: "Extol, [my] tongue, the mystery of the glorious body and the precious blood, which the fruit of a noble womb, the king of nations, poured out as the price of the world."

1. Traditional orthography as in Roman Catholic service books (stressed syllable marked with an acute accent on words of three syllables or more).

- Pange lingua gloriósi

- Córporis mystérium,

- Sanguinísque pretiósi,

- quem in mundi prétium

- fructus ventris generósi

- Rex effúdit géntium.

2. "Italianate" ecclesiastical pronunciation

- [ˈpandʒe ˈliŋɡʷa ɡloriˈoːzi

- ˈkorporis misˈteːrium

- saŋɡʷiˈniskʷe pretsiˈoːzi

- kʷem in ˈmundi ˈpreːtsium

- ˈfruktus ˈventris dʒeneˈroːzi

- reks efˈfuːdit ˈdʒentsium]

Article notes

- ↑ Allen 2004, pp. 15-16

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 17

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 26

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 27

- ↑ Sturtevant 1920, pp. 115-116

- ↑ Levy, Harry L. (1989). A Latin Reader for Colleges. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 150.

- ↑ Lloyd 1987, p. 80

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lloyd 1987, p. 81

- ↑ Lloyd 1987, p. 84

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 23

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 33

- ↑ Allen 2004, Chapter 1, Section v

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 39

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 47

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 51

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 56

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 59

- ↑ Ralf L. Ward, Evidence For The Pronunciation Of Latin, The Classical World, Vol. 55, No. 9 (Jun., 1962), pp. 273-275

- ↑ This simplification was already common in rural speech as far back as the time of Varro (116 BC – 27 BC): cf. De lingua latina, 5:97 (referred to in Smith 2004, p. 47).

- ↑ Clackson & Horrocks, pp. 273-274

- ↑ This approach is also recommended in the help page for the Latin Wikipedia.

- ↑ Gilbert, Allan H.: "Mock Accents in Renaissance and Modern Latin (in Comment and Criticism)", PMLA, Vol. 54, No. 2. (Jun., 1939), pp. 608-610.

- ↑ This change, like many of the others, dated from early mediaeval times and was by no means limited to Italy: "Already in the Old English period vowel-length had ceased to be observed except in the penultimate syllable of polysyllambic words, where it made a difference to the position of the accent ... Otherwise new rhythmical laws were applied, the first syllable of a disyllabic word, for instance being made heavy by lengthening the vowel if it were originally light (hence e.g. pāter ... for pǎter)" - Allen 2004, p. 102

- ↑ This pronunciation of mihi and nihil may have been an attempt to reintroduce /h/ intervocalically, where it seems to have been lost even in literary Latin by the end of the Republican period (Smith 2004, p. 48).

- ↑ In ecclesiastical Latin, following usage in Rome rather than in Italy in general, this intervocalic softening is very slight (Liber Usualis, p. xxxviij).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Liber Usualis, p. xxxviij

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 108

- ↑ Also criticised for various other anachronisms, not the least of which was the use of Latin instead of the official language of the eastern empire, Greek)

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 28-29

- ↑ Allen 2004, p. 119

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 See Pope, Chap 6, Section 4.

- ↑ "The word-divider is regularly found on all good inscriptions, in papyri, on wax tablets, and even in graffiti from the earliest Republican times through the Golden Age and well into the Second Century. ... Throughout these periods the word-divider was a dot placed half-way between the upper and the lower edge of the line of writing. ... As a rule, interpuncta are used simply to divide words, except that prepositions are only rarely separated from the word they govern, if this follows next. ... The regular use of the interpunct as a word-divider continued until sometime in the Second Century, when it began to fall into disuse, and Latin was written with increasing frequency, both in papyrus and on stone or bronze, in scriptura continua." E. Otha Wingo, Latin Punctuation in the Classical Age, Mouton, 1972, pp 15–16.

References

- Allen, William Sidney (2004). Vox Latina — a Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37936-9.

- Clackson, James; Horrocks, Geoffrey (2007). The Blackwell History of the Latin Language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-6209-8.

- Lloyd, Paul M. (1987). From Latin to Spanish. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8716-9173-6.

- Pekkanen, Tuomo (1999) (in Finnish, Latin). Ars grammatica — Latinan kielioppi (3rd-6th ed.). Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. ISBN 951-570-022-1.

- Pope, M. K. (1952) [1934]. From Latin to Modern French with especial consideration of Anglo-Norman (revised ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Smith, Jane Stuart (2004). Phonetics and Philology: Sound Change in Italic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199257736.

- Sturtevant, Edgar Howard (1920). The pronunciation of Greek and Latin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

See also

- Latin alphabet

- Latin grammar

- Latin regional pronunciation

- Traditional English pronunciation of Latin

- Deutsche Aussprache des Lateinischen (German) – traditional German pronunciation

- Schulaussprache des Lateinischen (German) – revised "school" pronunciation

External links

- "Ecclesiastical Latin". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1910. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09019a.htm?title=.

- Lord, Frances Ellen (2007) [1894]. The Roman Pronunciation of Latin: Why we use it and how to use it. Gutenberg Project. http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/7528?title=.

|

|||||